POWER PLAY: WHO REALLY RULES TODAY

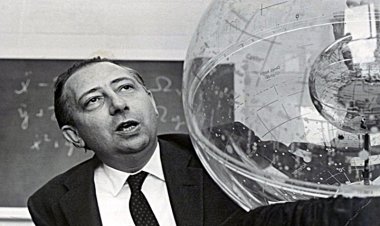

Frank Füredi

My Reflections on This Important Question For A Plenary Debate Held In London on 28 October 2023 At The Battle Of Ideas Conference

The fact that we have to ask the question of ‘who really rules today’ is interesting. Throughout history, the identity of those who ruled was not in question. Members of the ruling caste or ruling class or those endowed with ultimate authority openly acknowledged their status and, at times, even flaunted it. This question did not have to be posed by the sociologist C.W. Mills in his classic study, The Power Elite (1956).

The Power Elite is arguably the most influential sociological account of the workings of ruling class power in the United States in the 20th century. When I first read Mills in the 1970s, I was struck by his superb ability to capture the different dimensions of the constitution of American elite power in the 1950s. When I re-read the book a few years ago, I felt that it was still relevant, but as a very important historical text that could serve as a point of departure for making sense of what is distinct about elites in contemporary society.

Some of Mills's central arguments concerning the power elite's stability and cohesion come across as manifestly dated. Mills wrote of distinct and stable economic, political and military elites ‘who occupy the command posts’ and both rule and dominate society. Today, it is evident that the conditions that underpinned these stable command posts no longer prevail. Contemporary elites come across as insecure and reliant on administrative and technocratic solutions to compensate for their lack of authority. The military elite, which Mills assigned a prominent role, has lost its authoritative status. Cold War certainties that contributed to the power elite’s cohesiveness have given way to disorientation and a loss of elite self-consciousness. No doubt, if Mills were writing today, he would devote far more space to the role of the Cultural Elite than to that of the military.

Yet, The Power Elite retains considerable sociological significance because it anticipates trends that would fully crystallise and gain definition in subsequent decades. For example, Mills was one of the first observers to draw attention to the role of Celebrity and its relation to the Power Elite. Decades before the emergence of what is frequently described as Celebrity Culture, Mills drew attention to the Celebrity as a legitimator of elite rule. He wrote how elites of power share national acclaim ‘with the frivolous or the sultry creatures of the world of celebrity, which thus serves as a dazzling blind of their true power’. To be sure, Mills perceived celebrities as mainly playing the role of distracting the public from the exercise of real power. Today’s cohort of celebrities exercise cultural power in their own right. The celebrity is not only visible but also integral to the constitution of the elite. By drawing attention to the influence of celebrity culture in the early phase of its evolution, Mills was able to identify a development that would, over the decades to follow, become increasingly significant in Western societies.

Mills also anticipated the role of mass communication in securing elite authority a long time before the media acquired such a central role in underwriting the influence of contemporary elites. Contrasting the significance of the media for Mills’ power elite with its role today can offer interesting insights into an important dimension of 21st-century public life. Whereas in the 1950s, one of the roles of the mass media was to manage public consent, today, it significantly contributes to the construction of elite cohesion. For example, as Davis argued, the mass media helps sustain the ideological coherence of what he calls the ‘new managerial elite’ in Britain. With the erosion of the traditional foundation of elite power, culture and particularly cultural innovation has emerged as a predominant mode of elite self-understanding and self-definition.

One of the most significant insights Mills offers touches on the role of ideology in exercising elite power. Mills believes that without significant opposition to elite rule in the 1950s, those in power did not need an ideology. He noted that since the masses are fragmented and the intellectuals are timid, ‘we can readily understand why the power elite of America has no ideology and feels the need of none’. Elsewhere, he wrote, ‘Contemporary men of power, accordingly are able to command without any ideological cloak, political decisions occur without the benefit of political discussion or political ideas’.

The publishing of The Power Elite coincided with the emergence of the ‘end of ideology’ thesis. Whatever the validity of this thesis, the power elites’ apparent indifference to ideology was likely in part due to unique circumstances surrounding the Cold War. The fear and hostility provoked by the other side of the Cold War provoked an unusual degree of domestic consensus in Western societies. So long as the power elite was associated with the cause of the ‘free world’, it could rely on a domestic consensus and, therefore, did not need to draw on an explicit ideology to uphold its rule.

At this point, the authority of Western elites was sustained by their apparent moral superiority over the Soviet Union. Anti-communism was an important political resource on which the power elite could draw. It also endowed elites with a sense of cohesion. Most important of all, it provided them with moral legitimacy. Consequently, the Western power elites of the 1950s enjoyed a significant degree of stability and domestic support. However, with the disintegration of the Soviet Bloc, Cold War ideology lost its influence, forcing elites to look for other sources of legitimation. The quest for new sources of legitimation has been a recurring issue confronting 21st-century elites. Consequently, elites are continually confronted with the problem of authority.

The authority problem is closely related to the decline or gradual disintegration of the old establishment. Numerous studies suggest that Mills’s power elite or the old establishment in Britain has not been replaced by an equivalent group able to rule and assume responsibility and direction for the running of society. Following the sociologist Zygmund Bauman’s analysis, ‘liquid society’ is managed by ‘liquid elites’ whose institutional loyalties are fragile and short-term. Particularly since the 1980s, financialisation, deregulation, the rise of digital technology, and the diffusion of global power mean institutions that were hitherto critical for expressing elite interests in the political and economic domain have weakened. Mills’s Command Posts, the stable institutional underpinning of elite power, have lost much of their commanding influence. Matt Godwin has ably analysed this development in his important study, Values, Voice And Virtue.

Numerous studies claim that elite cohesion broke down in the 1970s.¹ Since then, it has struggled to sustain its sense of l’espirit de corps and authority. Indeed, today's elites appear to be far less effective than their counterparts in the 1950s and 1960s. Some observers assert that elites are increasingly fragmented and lack the capacity to exercise leadership and simply get things done. Elite fragmentation means that it is often unable to act effectively.²This development is particularly striking in relation to the United States, where the government is often paralysed in self-inflicted gridlock. Humiliating setbacks in Afghanistan, Syria, Iraq and Libya suggest that the so-called power elite is conspicuously unable to exercise its power effectively. As Lachmann pointed out:

‘America is unique among the world’s dominant powers of the past five hundred years in its repeated failure to achieve military objectives over decades. Those failures are even more extraordinary because they occurred in the absence of a rising military rival’.³

Without greater clarity about their position and authority, the elites find it difficult to endow power with meaning. Zaki Laïdi clearly articulated this point in his A World Without Meaning: The Crisis Of Meaning In International Politics (1998), when he wrote, ' Power is nothing when it has lost meaning’.⁴

Most explanations for the weakening of elite cohesion and its inability to formulate an authoritative shared outlook focus on the economic and social changes that kicked in during the late 1970s. While deregulation, financialisation, and the rise of digital technology contributed to the disruption of institutions, the erosion of institutional loyalties and the loss of institutional memory, there were other, arguably more important factors at work. These developments are, above all, the outward manifestation of the historic problem of elite legitimation. This problem is exacerbated by a loss of conviction in the values and outlook into which previous elites were socialised. Laïdi’s emphasis on the problem of meaning is closely linked to my thesis on the significance of the failure of elite socialisation in understanding this group's predicament.[vi]

To find a way of resolving the issue of legitimacy, the different groups of elites are continually experimenting with new institutional and ideological solutions. Governments have adopted an ethos of permanent change and reform. One of the paradoxical consequences of the ceaseless search for legitimacy is that the distinction between politics and economics has become blurred. In recent decades, the separation between economic and political power has become confused. The political elites often adopt a form of governance based on business models and business ideology, while the economic elites are increasingly drawn towards political and ‘ethical’ issues. So, while political governance refers to citizens as customers, stakeholders and clients, corporations adopt a values-oriented posture that is self-consciously distanced from traditional business ideology.

In contrast to Mills’s power elite, which supposedly did not need an ideology, its contemporary counterpart is continually in search of a creed through which to affirm its role as an elite. That is why ours is an era of values and mission statements. That is why so many of the disputes in the contemporary world are related to conflicts of values. It appears that culture has become a predominant mode of elite self-understanding and self-definition, particularly in the wake of growing threats to the traditional foundation of elite power. In this context, the cultural elites have come to play a critical role in the constitution of elite solidarity.

The role of the cultural elites is significant because, unlike their political and economic counterpart, they have retained – and arguably – even advanced their capacity to exercise cultural hegemony. Consequently, cultural institutions – such as the media and higher education – play a far more significant role in sustaining elite power than when Mills was working on his study.

The elite’s quest for legitimacy has led to a new form of technocratic governance, relying on dispersed policymaking and the ethos of managerialism, professionalism, and expertise. This development was strikingly confirmed during the Covid lockdown when the politicisation of public health ran in parallel with the medicalisation of politics. Though expertise plays an increasingly important role in legitimating decision-making, it lacks the moral depth necessary for endowing elites with the capacity to inspire society.

One of the distinct features of the current political landscape is that elites eschew the appearance of elitism. Unlike traditional elites, it rarely makes claims about its superiority over other members of society. In recent years it has become insecure about advertising its meritocratic achievements. Instead of highlighting its positive attributes, it has been drawn towards developing a negative version of authority. Its negative theory of authority highlights the intellectual and moral deficits of the public. It frequently draws attention to the fact that ordinary people often fail to act in their interest. It asserts that, unlike members of the elites, the masses find it difficult to deal with change and understand an increasingly complex world. Sections of the cultural elites perceive their role as ‘awareness raisers’. The activity of raising the awareness of the unaware masses attempts to endow their project with meaning. The sentiment that we are ‘not like them’ plays an important role in constructing contemporary elite sensibility. Drawing distinctions based on a claim to awareness is assisted through a symbiosis of popular culture and politics.⁵ Celebrities play an important symbolic role in promoting and highlighting the significance of this distinction.

It is difficult to designate any particular strata as a power elite today. It is important to note that a dominant elite does not necessarily constitute a ruling class. The exercise of ruling class power requires a capacity to draw on some source of authority. It requires an ethos of rule – that gives rulers a sense of cohesion and solidarity. Evidently, in the absence of a normative foundation or the exercise of elite power, they lack the moral legitimacy required to rule. Without a l’espirit de corps, there is no taken-for-granted pattern for rule-making. Instead of ruling, the dominant elites rely on rulemaking. The dramatic expansion of rulemaking helps to evade answering the question of how the rule is exercised.

Since power without meaning is difficult to exercise the dominant elites have opted to depoliticise public life. They constantly outsource decision making to non-elected, non-accountable apolitical bodies. Hence the constant expansion of state through partnership with NGOs, international organisations and public-private partnerships. This dispersal of decision making is motivated by the impulse of responsibility aversion. Through the framing of decisions as necessitated by a technical imperative, governing and ruling are become depoliticised. This displacement of government by governance leads to the transformation of citizens into clients, stakeholders, and patients. The exercise of technocratic governance assists the maintenance of a modicum of order. However, ultimately technocratic governance is underwritten by the cultural hegemony exercised by the elites. Coasting along rather than exercising iniative and ruling is the order of day in the contemporary Western world.

Society’s dominant elites are not simply being shy about not drawing attention to the status they really don’t know how to give a convincing account of themselves as legitimate rulers wielding power.

1

See for example

Mizruchi MS (2013) The Fracturing of the American Corporate Elite. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press and Lachmann, R. (2020) First-Class Passengers on a Sinking Ship: Elite Politics and the Decline of Great Powers, Verso:London.

2

Mizruchi MS and Hyman M (2014) Elite fragmentation and the decline of the United States. Political Power and Social Theory 26:

3

Lachmann, R. (2020) First-Class Passengers on a Sinking Ship: Elite Politics and the Decline of Great Powers, Verso : London, p.4.

4

Zaki Laïdi (1998) A World Without Meaning: The Crisis Of Meaning In International Politics, Routledge : London, p.16

5

See Daloz, J.-P. (2010). The Sociology of Elite Distinction. London: Palgrave Macmillan